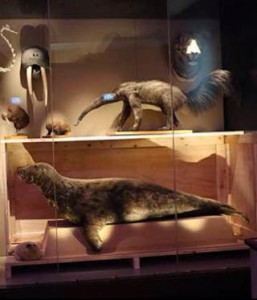

One of the reasons that Paddington Locks has been remember by generation of Warrington’s children is from a visit to Warrington Museum’s cabinets of curiosities and seeing the stuffed remains of a seal that was shot in the Locks in 1908.[spacer height=”default”]

The following stories about the fate of this seal has been kindly provided by Craig Sherwood. Documentation Access Officer at Warrington Museum.

Most of the information we have about the seal comes from newspaper reports of the time. The seal was first spotted on Tuesday 16th June and Warrington Guardian of 20th June 1908 reported that “Great excitement was caused on Tuesday by the discovery of a fish, said to be a porpoise or seal, in the Mersey near Warrington Bridge. Boats were brought out and it was pursued towards the Weir, when it turned round and proceeded in the direction of Walton Arches. Great efforts were made to capture it by men in boats. It made its appearance on the surface of the water at frequent intervals, and shots were fired at it, but it succeeded in getting away, The unusual scene attracted hundreds of people.”[spacer height=”default”]

On the morning of Wednesday 17th June 1908 the seal was captured at Paddington Lock (better known as Dobby’s Lock) on the Woolston New Cut, over two miles above the Warrington Bridge. To reach the cut the seal must have ascended Howley Weir, Latchford, which it probably did at high tide. It then unsuspectingly entered the lock where its presence was soon detected. The lock gate was promptly closed and the seal found itself trapped. The seal was then shot and it took the combined efforts of several men to haul it on to the bank. The capture soon attracted a lot of attention and large numbers of people visited the lock where the seal was placed on view at a small charge. The museum committee obtained the specimen and had it mounted by local taxidermist George Mounfield at a cost of £7 (roughly £400 today). It has been estimated that the exhibition of the seal brought in 14,000 extra visitors to the museum in the first year.[spacer height=”default”]

On the morning of Wednesday 17th June 1908 the seal was captured at Paddington Lock (better known as Dobby’s Lock) on the Woolston New Cut, over two miles above the Warrington Bridge. To reach the cut the seal must have ascended Howley Weir, Latchford, which it probably did at high tide. It then unsuspectingly entered the lock where its presence was soon detected. The lock gate was promptly closed and the seal found itself trapped. The seal was then shot and it took the combined efforts of several men to haul it on to the bank. The capture soon attracted a lot of attention and large numbers of people visited the lock where the seal was placed on view at a small charge. The museum committee obtained the specimen and had it mounted by local taxidermist George Mounfield at a cost of £7 (roughly £400 today). It has been estimated that the exhibition of the seal brought in 14,000 extra visitors to the museum in the first year.[spacer height=”default”]

Dimensions:

Nose to tip of tail 7 ft 6 in

Length to longest toe of hind foot 8 ft

Length of fore flipper 1 ft 2 in

Lenght of index toenail 2.5 in

Girth of body 4 ft 8 in

Length of head 1 ft 2 in

Length of incisor teeth 0.75 in

Length of hind flipper 1 ft 3 in

Width of hind flipper 1 ft 6 in

Length of tail 7 in

[spacer height=”default”]

Seals were certainly very unusual sights in the Mersey at the time – previous to this capture the only record of a Grey Seal in the Mersey that we know about was in the winter of 1860-1861 when one was captured in the Canada Dock, Liverpool. Although the Mersey would have been polluted at the time and would not have been a very inviting prospect to any large mammal the presence of a seal this far inland was considered particularly unusual because of the distance it had travelled from its native habitat. When the seal was captured contemporary Cheshire naturalist T.A. Coward (1867-1933) pointed out that grey seals are seldom seen on sandy coasts, preferring rocky coasts such as Western Scotland, and suggested this specimen may have bred on the North Wales coast.

As regards why the seal was shot I’m afraid there is no information on that. It’s possible that people were conc erned that it would interfere with waterborne traffic (it certainly would have been of concern to the lock keeper) but no mention is made of such concerns so it’s possible that we are projecting a practical justification on what may have simply been a case of spotting and hunting down a potential splendid natural history specimen or trophy. The newspaper reports of the time certainly don’t indicate that there was any effort to capture the seal alive or to drive it back out to sea and safety and it is entirely possible in the Edwardian period that the thought didn’t even occur. There is some evidence that a local crack marksman was sent for to shoot the seal which – given that it was captured in a lock – could indicate that people didn’t want it to suffer but it could equally indicate that people didn’t want to spoil the specimen. It’s difficult to be sure over 100 years later and one factor that complicates this whole element of the story even further is that there was a long tradition of parents bringing their children to the museum and telling them that their grandfather was “the man who shot the seal”. Unless there was an entire firing squad or a single remarkably fecund (!) marksman it’s likely that some of these parents were spinning a bit of a “tall tale”, one which has become so widespread it’s now impossible to conclusively establish the identity of the marksman in question or his motivation.

erned that it would interfere with waterborne traffic (it certainly would have been of concern to the lock keeper) but no mention is made of such concerns so it’s possible that we are projecting a practical justification on what may have simply been a case of spotting and hunting down a potential splendid natural history specimen or trophy. The newspaper reports of the time certainly don’t indicate that there was any effort to capture the seal alive or to drive it back out to sea and safety and it is entirely possible in the Edwardian period that the thought didn’t even occur. There is some evidence that a local crack marksman was sent for to shoot the seal which – given that it was captured in a lock – could indicate that people didn’t want it to suffer but it could equally indicate that people didn’t want to spoil the specimen. It’s difficult to be sure over 100 years later and one factor that complicates this whole element of the story even further is that there was a long tradition of parents bringing their children to the museum and telling them that their grandfather was “the man who shot the seal”. Unless there was an entire firing squad or a single remarkably fecund (!) marksman it’s likely that some of these parents were spinning a bit of a “tall tale”, one which has become so widespread it’s now impossible to conclusively establish the identity of the marksman in question or his motivation.

The seal continues to be a popular exhibit at the museum – now displayed in our Cabinet of Curiosity gallery. Some children still refer to it colloquially as “Sammy the Seal. One popular aspect of the specimen is it’s smile – especially after it had facelift around 17 years ago as the original taxidermist, George Mounfield, had simply blanked off the mouth with plaster. In 1999 the seal was conserved and a set of replica teeth were installed, modelled on an adult grey seal skull. The whiskers were replaced at the same time, actually using whiskers rescued from a tiger specimen!

For more information on Warrington’s Museum visit the website warringtonmuseum.